seven: my 2008 neurosurgery personal statement

[This is my actual personal statement from my 2008 neurosurgery residency application verbatim… plus my usual editorial commentary in italicized brackets.]

I have known I wanted to become a neurosurgeon since I was 20. Every step of my education since then has been aimed towards this goal.

[🤓]

As an undergraduate at the University of Washington (UW), I volunteered in a level I trauma center during the graveyard shift on Saturday nights and became familiar with brain injured patients and ICP monitoring.

[ICP = intracranial pressure. Hey premeds: if you can land one of these coveted late night weekend level 1 volunteer positions DO IT. On my first night I saw a stabbing victim, multiple MVA (motor vehicle accident) victims, a DPL (diagnostic peritoneal lavage) which is now obsolete, witnessed a shouting match between the neurosurgery resident and the senior EM resident, and pushed a gurney with the body of a 13 year old boy to the morgue. Often it is so busy you get to be elbow deep in the action. I also got a lot of cardio in by running labs back and forth, but you gotta pay your dues and what a small price to pay.]

PHOTO: The Saturday night wrecking crew at the Harborview Emergency Trauma Center (pre-med days).

I religiously attended the 3-4 hours of UW neurosurgery, neuropathology, and neuroradiology conferences held every Wednesday and observed neurosurgical procedures in the OR.

[TBH, I barely got up to go to my normal classes in undergrad, but when Wednesday rolled around I was an eager beaver and hopped out of bed at 5am in time to shower and catch a 6am shuttle to Harborview Medical Center to attend Dr. Winn’s legendary neurosurgery grand rounds at 7am and neuropath conference at 8am.]

I read every neurosurgery book I could get my hands on, from Fulton's Cushing biography to Greenfield. In medical school at the University of Virginia (UVA), I spent Saturday mornings at the resident teaching conference led by Dr. John Jane, Sr.; scrubbed in on procedures with the neurosurgical residents; and shadowed attendings in the clinic. Each hands-on experience with patients on the service and the dedicated faculty and residents verified that neurosurgery was my calling.

However, I recognized that it was not enough to merely practice neurosurgery. I believed it was also important to contribute to the advancement of the field. As such, clinically relevant neuroscience research became an early and enduring passion and I committed myself to a career in academic neurosurgery.

[n.b., If you want any chance of matching in neurosurgery, make sure to tell everyone on your interviews that you want to be an academic neurosurgeon… even though 90% of you will end up being spine jockeys in private practice. (No disrespect.)]

PHOTO: Scrubbed into a neurosurgery case at UVA as a 3rd year med student. Here, I’m helping out with the Stealth neuronavigation to verify the approach (by helping out, I mean staying out of their way lol).

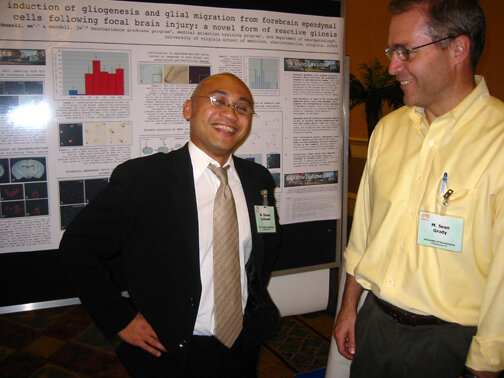

The genesis of such a goal occurred while I was an undergraduate researcher at the UW in the laboratory of neurosurgeon, Dr. M. Sean Grady (now Chairman at the University of Pennsylvania).

[Dr. Grady is retiring as Chair in July after 22 years!!!]

Dr. Grady's research was focused on hippocampal vulnerability after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Together, we published three articles and drafted a NIH RO-1 proposal utilizing a new murine TBI model.

[We didn’t end up getting the grant, but it was based on the new model I developed so I wrote 2 of the 3 aims and it was an invaluable experience.]

In addition to addressing the department on two occasions for Grand Rounds with my findings, I was invited to speak at two international conferences, including one as plenary session co-chairman.

[As an undergrad, I published an abstract that challenged a major dogma in the field and I was subsequently invited to co-chair a plenary debate session for a small (~100 people) international neurotrauma conference. The best part was heading out to dinner in beautiful Annapolis, Maryland with my panel afterwards (all professors) and them treating me like I was just a colleague. It was one of the first times I felt nurtured as an academic renegade and it was addictive. More often, my rogue views led to attacks by established professors. Don’t worry… these juicy stories are coming soon.]

PHOTO: Dr. Grady and I at my poster at the 2002 Neurotrauma Symposium in Tampa… my second year as a grad student.

This rich experience solidified my interest in pursuing a dual degree program (MD/PhD) for medical school so that I would have the best preparation for an academic career.

My scientific training continued to progress successfully thereafter, first as a Dean's Merit Scholar in the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at UVA and subsequently as a Cancer Research UK (CRUK) funded Senior Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Oxford (England, UK).

At UVA, I pursued basic research on the neuroinflammatory response after brain injury with my dissertation co-advisors, neuropathologist James Mandell, MD, PhD and the eminent cell biologist Rick Horwitz, PhD. Together we described for the first time the dynamic features of microglial responses after brain insults in live tissues. These findings have important implications for brain repair and the methods may be exploited for drug screening in diverse neurological disease models.

[My project was originally to study normal and “reactive” astrocytes as a way of “knowing the beast” since these cells (or their precursors) give rise to brain cancer. It changed mid-stream, however, when I saw a different cell in the brain (microglia) running circles around astrocytes in my migration assays. Therefore, I shifted the project to study how microglia migrate through the brain as a model for brain cancer invasion.]

PHOTO: This was my dedicated PhD bench space in Dr. Mandell’s lab… although I always used the adjacent space as well… it was where I kept my huge vibratome for tissue work.

The decision to immediately undertake postdoctoral training after graduating from UVA was difficult. However, I have witnessed junior neurosurgeons intent on an academic career fail to get a research program off the ground during the initial critical period after obtaining a faculty position. Therefore, I concluded it would be advantageous to solidify my research training prior to residency, including drafting at least one major grant proposal.

[Also, honestly, I really wanted to spend time studying abroad and was having research withdrawals.]

To this end, I was drawn in by the pull of Osler, Sherrington, Penfield, Cairns, and del Rio-Hortega and accepted an offer for a position at the University of Oxford.

[These Oxford men were as follows: Osler was the most famous physician of his time and mentored the father of neurosurgery (Harvey Cushing), Sherrington won the Nobel Prize for describing the first reflex, Penfield studied under Sherrington and later founded the Montreal Neurological Institute, Cairns was the leading UK neurosurgeon of the time who operated on Lawrence of Arabia, and del Rio-Hortega discovered microglia… the cell I studied for my PhD.]

There, I worked with Prof. Ruth Muschel, MD, PhD to establish a research program on brain metastasis in the historic Gray Institute for Radiation Oncology and Biology.

[That’s Gray as in Louis Harold Gray the physicist who studied the effects of radiation on tissue and whose name is now an SI-unit for quantifying absorption of ionizing radiation (Gy).]

I was soon elected to a competitive Junior Research Fellowship at Brasenose College (one of the oldest constituent colleges of Oxford University) and after 2 years was vetted for an Assistant Professorship within my department.

[I actually had two faculty positions in play at one point, but that’s a story for another time. Also, two fun facts… First, Brasenose College, more formally known as “The King’s Hall and College of Brasenose” (and more commonly referred to as “BNC”) was consecrated by Henry the VIII in 1509. Second, the Junior Research Fellowships (or JRFs) are the most prestigious awards for postdoctorates at Oxford (and the “other place”, aka Cambridge). There are only around a dozen elected each year at the entire university. There is no equivalent rank in the states, but it is widely considered a fast-track to a faculty position at Oxford (and the “other place”).]

PHOTO: Posing in front of high table at Brasenose College, Oxford. As a JRF I could dine at high table any night of the week. Real secret society/Hogwarts/Order of the Phoenix shit… more on that soon…

During this time we discovered fundamental mechanisms of brain metastasis formation and vascularization and advanced new perspectives in the diagnosis and clinical treatment of cancer patients. In addition, I achieved my initial goals and have drafted outlines and possess extensive preliminary data for R01-type grants in the fields of TBI and neuro-oncology. I hope to continue with one of these research avenues during residency training, ideally with extramural funding based on my proposals such as a mentored K08 award.

[I always feared getting scooped, but honestly, still no one has pursued any of it even after over a decade. Maybe I’ll retire at Oxford and revive these studies then…]

PHOTO: My Oxford postdoc work got featured by the BBC News just after I left.

In closing, although I have undertaken an unorthodox path, the accomplishments I have attained are objective measures of my determination, drive, and desire to succeed as a neurosurgeon-scientist. Many individuals over the past 13 years have been skeptical of my goals; indeed, some have actively attempted to dissuade me from pursuing them. However, I have persevered, continually drawing upon inspiration from my mentors who have shown me by example that a career in academic science and neurosurgery are not mutually exclusive, but can be synergistic.

[I believe this to still be true. My situation was just a little more complicated as I’ve written about previously.]

I welcome the clinical and scientific challenges ahead with enthusiasm and look forward to the start of training in July.

[DOH!!! We started 2 weeks earlier! And my first day as an intern I found out I was on call for general surgery just as I was getting ready to go home! But the good news is that I got to “fly solo” on a laparoscopic appendectomy at midnight on a 14 year old kid. Even though he was on a different service, I went and visited him in the morning. It was gratifying to see him sitting up and laughing with his family after what was no doubt a pretty rough night. ]